Design Thinking & Science

Catalyzing innovation in science with design thinking approaches

We all know how the scientific method works: you come up with a hypothesis, perform experiments, collect results, and then refine the conclusions. But scientists also realize this isn’t how many research findings actually come about. Are there other mechanisms by which scientists can push innovation in the lab? Wendell Lim and his lab members have partnered with the design firm IDEO to try and infuse 'design thinking' approaches into the way they conduct their research. This unique collaboration was recently featured in a news analysis in Cell.

See the article here.

Find out more about the UCSF | Lim Lab Partnership with IDEO here.

Excerpt from Synthetic Aesthetics (MIT Press, 2014)

By Wendell A. Lim

By Wendell A. Lim

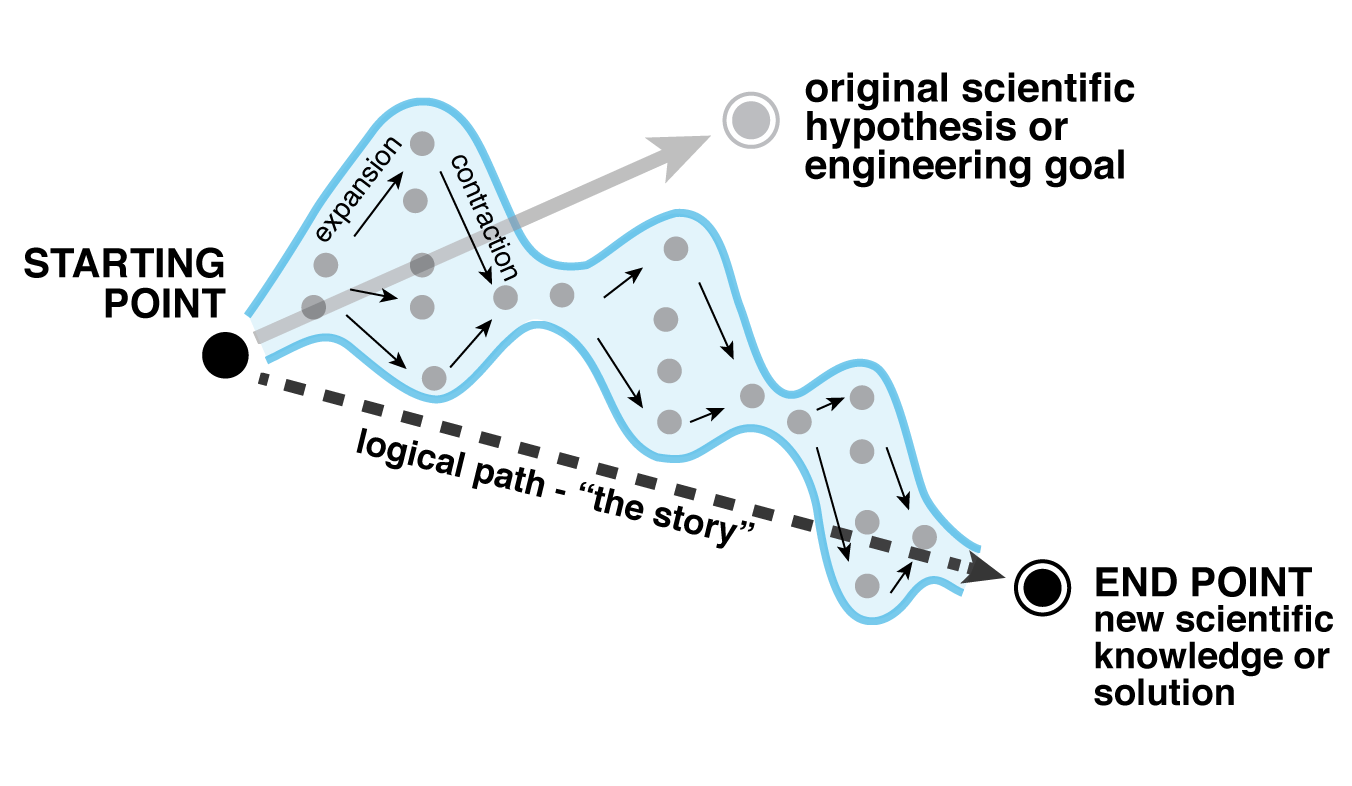

Science tends to be viewed as one of the most rigorous and logical of human endeavors. Yet this popular impression of the practice of science is based on how it is presented to us, rather than how it is practiced in reality. The great French molecular biologist and 1965 Nobel laureate, François Jacob, wrote of the two faces of science: “day science,” the official science of articles, seminars, and textbooks, and “night science,” the world of confusion, doubt, sweat, and inspiration. He suggested that in reality, path-breaking scientific research emerges from “a jumble of untidy efforts, of attempts born of a passion to understand.” These efforts are then written up in such a way as to depersonalize the achievement and “replace the real order of events and discoveries by what would have been the logical order, the order that should have been followed had the conclusion been known from the start.”2 When a scientific project is completed, and some nugget of knowledge has been gained and verified, it is much more effective to communicate this knowledge in the simplest, most linear manner—in other words, via a revisionist description that differs significantly from the wandering path that scientists actually followed. This is not misguided—to complicate further the already formidable challenge of clearly transmitting scientific facts would be counterproductive. But there is a resulting trade-off: After years of absorbing scientific facts taught in this way, it can be a considerable challenge to learn how to practice the art of scientific research, which is, in actuality, much messier.

The reality of Jacob’s night science is that its practice is much more iterative, uncertain, and fitful, but at the same time much more exciting and personally satisfying. It really is a creative process, full of struggle punctuated by inspiration. Like all creative processes, design is involved at all steps. Take the ostensibly straightforward, logical formulation of the “simplest hypothesis that can explain the data.” How do scientists formulate (or design) the simplest hypothesis? Often, no single hypothesis is clearly the simplest, so how are these hypotheses broken up into families with common core elements? How do scientists figure out which ones are most easily testable or which ones, if disproved, would be most informative in limiting other possible models? It is not as straightforward as it would seem, but grappling with these questions is incredibly rewarding

Science as a craft is at once both enormously creative and cautious. The importance of producing sound, evidence-based conclusions leads many within the scientific community to view speculation and conjecture with suspicion. Yet in order to derive these sound, testable conclusions, scientists need to know what questions to ask and what experiments to do next; for those purposes, speculation is essential. Night science is extremely difficult to practice and to teach—examining it as a creative process could be very fruitful. But instead of thinking more critically about night science—dissecting it and breaking it down analytically as designers have done with their practice—there is a tendency to suppress it and replace it with a sanitized day-science caricature..